March 19, 2007

By John Robert Colombo

When the telephone rings, I am never quite sure who is phoning me, so I answer tentatively. It is known that I collect Canadian quotations and publish these “quotable quotes” in reference books like The Penguin Dictionary of Popular Canadian Quotations. People – sometimes well-known people – phone me out of the blue to draw my attention to remarks of theirs that I should consider including in my next collection. It is also known that I collect Canadian ghost stories and publish them in collections like Terrors of the Night and The Midnight Hour. When someone phones who has a scary account to share with me, I check the time on the clock. I allow ten minutes for an account of an encounter with a ghost or spirit, or five minutes for an encounter with a UFO. But if the caller has a European accent, I listen carefully to the intonation, for the caller may be a Bulgarian (I have edited five anthologies of the literature of Bulgaria in English translation), a Romanian (a volume of my poetry was translated into that language and issued in Bucharest), or a Hungarian (I have assisted in the publication of five books of Hungarian-Canadian literature). When I am asked if I speak these languages – Bulgarian, Romanian, or Hungarian – I always admit the truth: No, no, no. I point out that, surely, it is enough that although I was born in Canada – in Kitchener, Ontario – I am the living embodiment of Canadian multiculturalism because of all my ancestries: four ethnically different grandparents – Greek, German, Italian, French-Canadian. So I answer the telephone tentatively. But the chances are that the phone caller is not a New Canadian but one of our three children (whose backgrounds are even more diverse than my own background and my wife’s Polish and Jewish background). However, I do pay attention to all the callers, especially the Hungarian ones.

When the telephone rings, I am never quite sure who is phoning me, so I answer tentatively. It is known that I collect Canadian quotations and publish these “quotable quotes” in reference books like The Penguin Dictionary of Popular Canadian Quotations. People – sometimes well-known people – phone me out of the blue to draw my attention to remarks of theirs that I should consider including in my next collection. It is also known that I collect Canadian ghost stories and publish them in collections like Terrors of the Night and The Midnight Hour. When someone phones who has a scary account to share with me, I check the time on the clock. I allow ten minutes for an account of an encounter with a ghost or spirit, or five minutes for an encounter with a UFO. But if the caller has a European accent, I listen carefully to the intonation, for the caller may be a Bulgarian (I have edited five anthologies of the literature of Bulgaria in English translation), a Romanian (a volume of my poetry was translated into that language and issued in Bucharest), or a Hungarian (I have assisted in the publication of five books of Hungarian-Canadian literature). When I am asked if I speak these languages – Bulgarian, Romanian, or Hungarian – I always admit the truth: No, no, no. I point out that, surely, it is enough that although I was born in Canada – in Kitchener, Ontario – I am the living embodiment of Canadian multiculturalism because of all my ancestries: four ethnically different grandparents – Greek, German, Italian, French-Canadian. So I answer the telephone tentatively. But the chances are that the phone caller is not a New Canadian but one of our three children (whose backgrounds are even more diverse than my own background and my wife’s Polish and Jewish background). However, I do pay attention to all the callers, especially the Hungarian ones.

I do this because I have a soft spot in my heart for my Hungarian connection, which is the first that was formed and the one that is associated in my mind with enduring friendships with some wonderful and talented people. As a result of this association, my wife Ruth and I have twice been able to visit Budapest. Here is how that connection came about.

The first Hungarian I ever met was George Jonas, the author of numerous books and the social-affairs columnist for the National Post. Forty-six years have passed since Jonas walked into the foyer of The Ryerson Press, the Toronto publishing company where I was employed as a novice editor between 1960 and 1963. Shortly before that he had immigrated to Canada; now he was then driving a taxi for a living in Toronto. Despite his hesitant yet insistent English, laden with Hungarianisms, he was determined that Ryerson should consider for publication his manuscript of translations of poems composed by a fellow countryman named Miklos Radnoti.

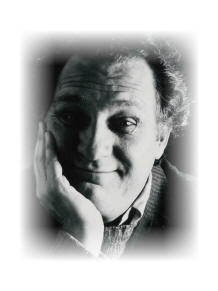

George Jonas. Photo by Kevin Van Paassen/National Post

Until that time I had never heard of Radnoti, a victim of World War II; indeed, until that time I had met only one other Hungarian, Mr. Jonas being the second! But at a glance I could tell that Radnoti’s poems, at least in Jonas’s English versions, were not going to be viewed favourably by the Publishing Committee. Still, I was intrigued by this lanky young Hungarian whose teeth were as bad as his English, but who had a Byronic manner and at a youthful age expressed particularly pronounced views on society and the arts. He made an impression on me, so we made an appointment to have coffee outside office hours.

Thus began a friendship that has waxed and waned over the next four decades. We and our wives socialized and the two of us worked on translations of Radnoti’s poems as well as on those of a dozen other Hungarian bards. It was my introduction to European literature in translation and it was Jonas’s introduction to the Canadian literary and broadcasting scene. On one occasion, at a party in our living-room, he met Irving Layton, Earle Birney, and Leonard Cohen. That’s a Hat Trick! Our translations appeared in a few “little magazines” of the day, but it was not until 1995 that a book-length collection of these versions titled Some Hungarian Poets was issued.

In the meantime Jonas gave everyone who would listen first-hand accounts of the evils and ironies of everyday life in a small Central European country under the rule of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union. He sounded a tocsin but it was taken with a grain of salt by most of his Canadian-born associates. In fact, at the time he sounded more like a contrarian than he did a political pundit or social prophet. It took him a decade or so to define himself as a “classical liberal” and to discover that there existed an emerging a genuine alternative to the country’s semi-socialism, its so-called mixed economy, and its vague and voguish liberalism – and this was the neo-conservative movement. Someone once said, “A conservative is a liberal who has been mugged.” Jonas had been mugged (after all, he had to escape from his native land) but he let it be known that it was not going to happen to him again. Neo-classic liberal indeed!

Jonas has made distinguished contributions in a number of areas. He is a poet of individuality and ability whose four collections – The Absolute Smile, The Happy Hungry Man, Cities, The East Wind Blows West – deserve to be widely read. My particular favourite is Cities, especially the title poem in which he describes himself as being in no city at all – in a passenger liner in the stratosphere high above the Earth. I am only sorry he has written (or at least published) so few volumes of verse. His poetry is demanding because it reminds his readers that his ideas will expand and deepen theirs.

Jonas became a script-reader for the CBC, then a writer and producer of a series of award-winning radio and television programs of merit, intelligence, and resonance. The Scales of Justice series set a highwater mark for real-life drama in terms of human interest, production values, and social issues. Two collections of these scripts were published. No subsequent series, either documentary or dramatic, has come anywhere near attaining these levels.

Jonas turned his attention to the impact of criminal activity on the justice systems of democratic societies. With his then wife Barbara Amiel, he collaborated on By Persons Unknown, a work of considerable facility which deservedly earned the authors an “Edgar” from the Crime Writers of America for true-life crime reportage. He collaborated on a book with criminal-law advocate Edward L. Greenspan which is more than a biography for it is a consideration of “the case for the defence,” i.e., the signal importance of civil and personal liberties and human rights, a concern that would become increasingly important to the author and also to custodians of justice and defence over the years.

In the same vein, but with a political agenda, is Jonas’s Vengeance, which raises the lethal consequences of “moral equivalence,” i.e., the failure to discriminate between action and reaction. This non-fiction account of the massacre of Israeli athletes and the aftermath was the basis of a quality television series and then Steven Spielberg’s feature-length motion picture. Issues discussed in the book continue to be raised throughout the Western world and the Middle East.

Jonas has at his disposal the sharp eye and the equally sharp pen of the political and cultural journalist for the significance of forms of evasion and exoneration assumed by society. A Passion Observed is, surprisingly, a tensely written account of the philosophy and psychology of sports competition (in terms of a motorcycle racer). Less intense are two collections of columns, Crocodiles in the Bath and Politically Incorrect, which nevertheless give expression to the author’s near-libertarian views. (I find these essays a quarry for “quotable quotes” for my collections.) His editorial columns in the National Post expand the notion of social-political commentary to include the arts and values of democratic and totalitarian societies.

If Jonas was once mistakenly regarded as a “contrarian,” he is now erroneously regarded as a “posterboy” for neo-conservative values. Both views are distortions. It is simpler to say he is immersed in realpolitik, one of the few public intellectuals in English Canada to be so committed. (Perhaps I should qualify that: Jonas follows the same path as author George Woodcock, who was much influenced by the anarchistic movement, and philosopher George Grant, the country’s leading disciple of Leo Strauss. A like-minded colleague is expatriate columnist David Frum. Then there are the “neo-cons,” the head-honcho being Tom Flanagan.) The health of society and the ailments that afflict individuals, both physical and mental, are discussed in his stylishly written memoirs, Beethoven’ s Mask. His latest book, which I have yet to read, is a collection of essays titled Reflections on Islam.

Jonas was largely responsible for bringing to national attention the presence in Canada of the famous Hungarian émigré poet George Faludy, who lived in Toronto for a decade and a half and even acquired Canadian citizenship. Faludy’s work, translated by Jonas, impressed a dozen or so Canadian poets and writers (including Fraser Sutherland, Dennis Lee, and Robin Skelton) who then co-translated Faludy’s poems. I published two collections of them and last year combined them as Two for Faludy. It was through Jonas that I met other Hungarians whose friendships I cherish.

Among them are the late memoirist George Gabori and his wonderful wife Ibi; Stephen Vizinczey, the author of In Praise of Older Women as well as collections of stylishly written essays; Magda Zalan, the prima donna of impresarios with her “Podium” series devoted to music and the spoken word; the multi-talented Robert Zend and his French wife Janine. Then there is Dora de Pédery-Hunt the medalist and Andrea Jarmai, the tireless poet and organizer of poetry readings (and the best translator of Faludy’s work ever). My interest in metaphysical books and ideas led me to meet Daniel Kolos (a poet who calls himself “a practising Egyptologist” but whom I regard as “a mystagogue”). From One Child to Another is the title of his newest book of poems. It includes an informative reminiscence of Faludy that is nine pages in length. On one of these pages he writes:

You began to preach the end of the world

both with your poetry and your repartee

and privately admitted that you practised magic,

though your public persona was entirely logical;

within, you were a mystic like Rumi,

but only your eyes danced.

That is a fine last line! His eyes did dance!

I have discussed George Jonas at length in this reminiscence because he was the first, “the only first,” as they say. Should the occasion warrant, there will be future reminiscences of the Gaboris, Vizinczey, Zalan, the Zends, Jarmai, and Kolos. But only if the occasion warrants … and if the phone rings and a friendly voice with a Hungarian accent inquires, “Are you the Colombo who translates Hungarian poetry?”

Visit the website of John Robert Colombo: www.colombo.ca