From humble beginnings in Hungary to the top of the podium at the Olympic Games, Valerie Gyenge’s adventure really began when Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest.

Joe O’Connor, National Post

Published: Saturday, December 02, 2006

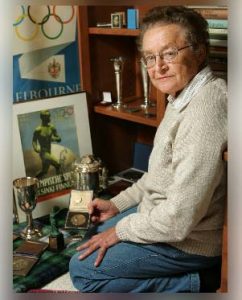

TORONTO – She keeps her Olympic gold medal in the blue velvet box it came in. Its hinges were damaged during a visit to her grandson’s grade school for show and tell.

TORONTO – She keeps her Olympic gold medal in the blue velvet box it came in. Its hinges were damaged during a visit to her grandson’s grade school for show and tell.

The old box has since been reinforced with a strip of black electrical tape. On the inside of the lid is a button, a gag gift from an old friend. It reads: “I used to be famous.”

Valerie Gyenge occasionally reaches for her Olympic treasure when she is having a bad day. It reminds her that she did something extraordinary with her life, and that she had a dream, once, and that she chased it until it came true.

She has done so much more with her life since then, as a mother to two daughters, as a grandmother, as a professional photographer, as an author, and as a legend in Hungary, the country of her birth.

But in Toronto, Gyenge is anonymous, just another older lady you might pass on the street and not even see. Take the time to stop and talk awhile and the pixie-like 73-year-old with the iron-grip handshake will tell you all about those terrible weeks in 1956 when the Soviet tanks changed the world she knew forever and a promise kept brought her to Canada.

“I’m very old now, and it was such a long time ago,” Gyenge says from the living room of the apartment she rents on a quiet cul de sac in north Toronto.

She takes her guest’s coat, offers him coffee and then curls herself into a chair and begins to speak. Her English is clear, if flavoured by a strong Hungarian accent.

Gyenge remembers the exact moment when she decided to become a swimmer. Her parents owned a grocery store in Budapest before the Second World War, before the Soviets came, before freedom failed Hungary.

The family would pack up on summer weekends and head to a rustic cabin on the shores of Lake Balaton. “I think I was around nine years old,” Gyenge says.

“A very good-looking man came down to the beach, dove in to the water and swam a beautiful freestyle, and I said, ‘That’s it: I want to be a swimmer.'”

Hungary emerged from the Second World War as a satellite nation in the Soviet Empire. Communism, though, was kind to some. As an elite young talent on Hungary’s national swim team, Gyenge, a freestyle specialist who excelled in the distance events, enjoyed a life of relative privilege. By age 18, she had seen Paris, been to the Louvre and stood beneath the Arc de Triomphe.

Hungary emerged from the Second World War as a satellite nation in the Soviet Empire. Communism, though, was kind to some. As an elite young talent on Hungary’s national swim team, Gyenge, a freestyle specialist who excelled in the distance events, enjoyed a life of relative privilege. By age 18, she had seen Paris, been to the Louvre and stood beneath the Arc de Triomphe.

“Nobody ever saw chocolate and oranges in Hungary, and we would get chocolate and oranges,” Gyenge says.

“We travelled. We received extra food, extra money, and it was very nice to be comfortable.

“But I wasn’t interested in the politics. All I was interested in was swimming. The Olympics was my dream.”

She made it there in 1952. The Summer Games in Helsinki were the first at which the Soviet Union and its puppet republics were represented. To separate East from West, the Olympic organizers built two athletes’ villages.

Gyenge was just a teenager. She remembers getting bused back and forth to the outdoor competition pool with her teammates, accompanied by some ever-watchful members of the Hungarian secret police.

Helsinki was supposed to be her warmup for the Melbourne Games in 1956, a chance for a raw teenager to gain some experience and measure her talent against the world’s best.

No one expected Gyenge to make the final in the 400-metre freestyle. And no one expected her to actually win. But whatever nerves the tiny Hungarian with the dark curly hair may have had melted away at the sound of the starter’s pistol.

Gyenge understood that the favourites — Evelyn Kawamoto of the United States and her Hungarian teammate Eva Novak — were fast starters. She knew she could never beat them in a sprint.

Her strength was her endurance, so Gyenge waited. She made her move at the 250-metre mark, and the next thing she knew she was on the top step of the podium listening to the Hungarian national anthem with tears streaming down her face, a gold medal in her palm, and an Olympic record in her pocket.

Unheralded Hungary won 16 gold medals in 1952 to finish third behind the United States and the Soviet Union. A special train was arranged for Hungary’s returning heroes. A giant number 16, rendered in gold numerals, was affixed on the front of the engine.

The train stopped in every town, village, and hamlet. At every point, people rushed the platform to greet their champions with flowers, songs and tearful thanks.

The train stopped in every town, village, and hamlet. At every point, people rushed the platform to greet their champions with flowers, songs and tearful thanks.

Gyenge and the other athletes were viewed as a healing balm for a country caught under the thumb of a brutal despot, Matyas Rakosi, who governed using the tools of terror, secret police, kangaroo courts and concentration camps.

“When we arrived in Budapest, there were thousands of people in the street,” Gyenge says. “We marched from the railway station to Stalin Square — it’s not called that any longer.”

For the next four years, the surprise star of the Helsinki Games trained, won races, set world records, and worked in a photo lab when she was not in the pool. She also fell in love with a handsome water polo player named Janos Garay.

Garay was good at his sport, but not good enough to make the national team. So he studied, became an engineer and asked Gyenge — his fiance — to promise him something: If he ever managed to escape to the West, would she defect when her travels as a swimmer took her outside Hungary?

“I was young and in love, and so of course I said yes,” Gyenge says.

She had no idea how soon the promise would be tested.

On October 23, 1956, tens of thousands of protestors flooded the streets of Budapest demanding an end to Soviet rule. They wanted free elections. They wanted a free press. They wanted the Soviets to get out of their country.

The day started with a peaceful rally. It ended with running street battles between the demonstrators and the pro-Communist Hungarian police.

Not far from the unfolding chaos was the Hungarian Olympic team. The 1956 Summer Games were set to open in Australia on Nov. 22, and the squad had gathered in the hills above Budapest for a final training camp.

“They wouldn’t let us leave our hotel,” Gyenge says. “We didn’t know anything.”

Unable to train and under house arrest, the athletes waited and worried. Down below in Budapest, the violence escalated. The Soviet tanks were called in, and then, miraculously, they pulled back from the capital on Oct. 30.

The Olympic team was promptly shuttled to Czechoslovakia. Two planes were chartered to fly them to Australia. With the pilots requiring mandatory breaks under international aviation law, the trip became a world tour of sorts, with Team Hungary touching down in Karachi, Istanbul and Singapore.

In these out-of-way places, the athletes were able to buy newspapers. They saw pictures of the Soviet tanks that, after a brief reprieve, had rolled in to Budapest to crush the revolution.

“Everybody was a nervous wreck because everybody had loved ones back home,” Gyenge says. “We saw the pictures of wounded and dead in the street, and the tanks, and the ruined houses. The team officials said it was just the capitalist press playing games.”

There was no hiding the truth once the team reached Melbourne. The revolution had failed. Thousands had been killed, and thousands more were fleeing the country.

Gyenge remembers a Hungarian gymnast scaling a flagpole that was flying the Soviet era Hungarian flag, which featured a hammer and sickle. Her countryman cut the hated symbol out of the standard.

The Hungarians held a team meeting on the eve of the Opening Ceremony. They voted to wear the emblem that had been adopted by Imre Nagy’s short-lived-liberalizing government on their uniforms, along with a black ribbon.

It was around this time that a telegram arrived at the Olympic village. It was from Garay. He was safe in Vienna and on his way to Toronto. He asked his fiance to join him there.

It was all arranged. Garay’s first cousin was a Hungarian ex-patriot living in Toronto named Peter Munk. The future captain of Canadian finance knew some people, who knew some people at the Toronto Star.

Milt Dunnell, the paper’s sports editor, was in Melbourne covering the Olympics. He made contact with Gyenge. Dunnell had a plane ticket, an entry visa, everything she would need.

The only condition: Gyenge’s escape was to be an exclusive story for the Star, and so she was asked to keep quiet around the other reporters.

It was not easy. The Hungarians were celebrities in Melbourne. Rumours were whirling about how 10, 20, maybe even as many as 100 members of the team would stay in Australia, or head to the West at the conclusion of the Games.

Everything was moving so fast, and the defending Olympic gold medallist in the 400-metre freestyle was tremendously conflicted. Gyenge feared that going to Canada would mean never seeing her parents and brother again.

The stress she was under showed up in her results. Gyenge failed to make the 100-metre freestyle final, while the Hungarian relay squad sank to seventh place in the 4x100m final.

Gyenge did manage to qualify for the final eight in her signature event.

“I don’t even remember how I got to the blocks,” she says. “And then I heard the starter gun, and so I jumped in the pool and tried to pull myself together.”

She couldn’t do it. Her arms felt like anchors. She struggled to breathe. Gyenge limped home in last place. She felt numb. Four years of training and then, disaster.

Even worse, the end of the race did not ease the sea of anxiety she floated in.

“There were so many things and so much agony over what I should do,” Gyenge says.

And then another telegram arrived. Gyenge’s mother was offering her daughter her blessing for the move to the other side of the world.

Valerie Gyenge landed in Vancouver on Dec. 10, 1956. She was wearing her Hungarian national team uniform beneath a raincoat, and carrying a small suitcase with a couple of warmup suits, some bathing suits and a few towels inside.

The next day she flew to Toronto.

“When the plane took off from Vancouver, I couldn’t understand the distance,” she says. “We were flying all day. It was late afternoon when I arrived, and it was bitterly, bitterly cold.”

Janos and Valerie were married soon after she arrived. A group of Canadian swimmers threw Gyenge a bridal shower before her wedding day, an event she recalls with fondness since their gift to her was a proper winter coat. “I was saved,” she says with a laugh.

The newlyweds moved in to an apartment in Rosedale. Gyenge did not speak a word of English, but she was able to find work washing and drying photographic plates at an advertising agency for $30 a week. Garay caught on as a draftsman with an engineering firm and, gradually, he started doing well.

“I was terribly homesick,” Gyenge says. The homesickness would disappear with the birth of her eldest daughter, Judy, in 1960. By then, Janos was a success, and the young family began to thrive in its adopted home.

In 1964, the Hungarian government offered amnesty to all those who had fled the country in the wake of the Soviet crackdown of 1956, including the 50 athletes who defected at the Melbourne Games. Gyenge returned to Budapest that year to visit her parents and younger brother. “It was great to see my parents and my old friends and my home,” Gyenge says. “But I never thought for a minute that I would go back there to live.”

And she never did.

The 1952 Olympic champion still swims three times a week, turning laps in the fast lane at a community centre not far from her home. Gyenge also does yoga, walks her grandson, Travis, to and from school, and she writes.

She has published two novels plus a collection of photographs. The sales here have never amounted to much, but in Hungary, where they still remember the young champion with the dark curls, Gyenge’s books have sold well.

She published her second in 2005. It is a love story called The Promise, and it is based on the swimmer’s life and the turbulent times that brought her to a new land.

“It was Dec. 11, in the afternoon, when I came to Toronto,” Gyenge says. “That was 50 years ago. It has been a long life. I have lived a good life.”

“Reprinted with permission of the National Post, copyright 2007”